The Metropolitan Oval Academy

There’s something about the place that draws soccer people to it. It’s somewhere that soccer people can feel at home. Where the ghosts of bygone games and a bygone era assure you that there is a sturdy past on which to build the future of American soccer. Paul Gardner, Soccer America

Visit the Metropolitan Oval in Queens today and you’ll not only see excellent youth soccer, but you’re also likely to hear animated cheering in Greek, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and English. The range of languages reminds us that soccer is the world’s sport; love of the game and the kids playing it is something we all have in common. The spectacular view of Manhattan may also remind some that soccer has found a world-class home in America’s greatest city. But it’s a home it had to fight for.

Our History

The history of the Metropolitan Oval is the history of soccer in America. It’s the story of identity, immigration, and the American Dream. The dream began shortly after World War I when a wave of ethnic Germans from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire known as German-Hungarians immigrated to the United States looking for job opportunities no longer available in Europe. Many of the new arrivals settled in major cities like Philadelphia, Cleveland and Chicago, but most found themselves in the shadow of Manhattan in Ridgewood, Queens, already home to a bustling German community with a German language newspaper, beer gardens and five major brewing companies limping through prohibition (1920 to 1933) by selling low alcohol beer.

“The Dust Bowl”

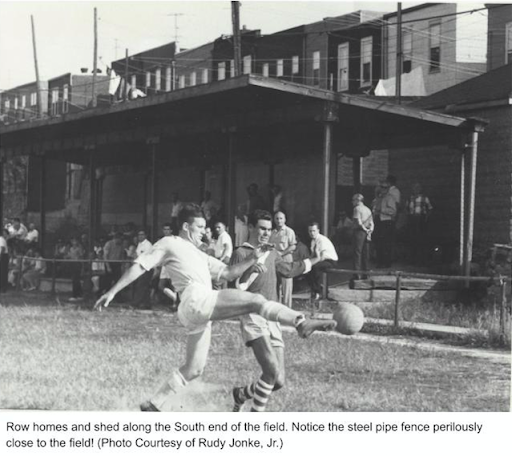

Today, Met Oval can legitimately claim to be one of the oldest continually used fields in the country. Boasting a state-of-the-art turf with the give and feel of traditional grass, it’s a far cry from the rocky sandlot players experienced from the 20s until the first artificial surface was installed in 2001. The German-Hungarians tried for decades to plant grass at the Oval but could only manage a few lonely clumps in the corners. In a phone interview, former Blau Weiss Gottschee great, Ricky Kren, called it “The Dust Bowl,” and Soccer America Columnist, Paul Gardner, described it affectionately as “a dump.” According to Kren, Pops, the caretaker in the 60s and 70s, would use an old Ford to drag a metal mattress box spring across the field to get rid of the rocks before watering it by hand with a garden hose to keep the dust down. If a player wasn’t cut to ribbons by the rocks, the goals had jagged metal fencing for netting and there was a steel pipe fence ringing the field just yards from the touch line that could really ruin their day. While the Oval may have been more “Thunderdome” than “Field of Dreams,” former players recalled the setting was hard to beat and for some it was even inspiring.

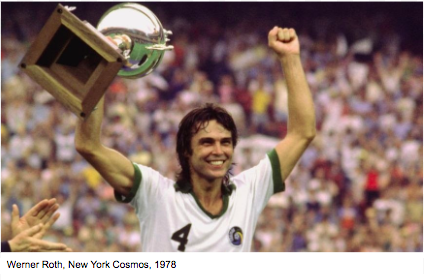

Hemmed in by row homes to the South and East and the Long Island Railroad tracks to the North (where many a ball went missing), Met Oval had, and still has, a unique neighborhood setting. To the West is a magnificent view of midtown Manhattan, including the Empire State and the Chrysler Buildings. In a phone interview, German-Hungarian legend, Werner Roth, remembered how, as a kid playing at the Oval, that view inspired him to think of a world beyond the insulated community of Ridgewood. Roth became the first person in his family to earn a college degree when he graduated from Pratt Institute where he studied architecture.

Kids play during halftime in 1962 as fans stream down the hill to the concession stand for beer and brat. (Photo Courtesy of Paul Gardner)

The Players and the Atmosphere

Roth was lucky to be in America at all. His German-Hungarian family came to Queens in the early fifties as refugees from what is now Serbia and what was then the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia. In fact, their immigration was only possible because of German-Hungarian Club President, Peter Max Wagner. In 1946, Wagner formed a benevolent society to send food aid to the displaced people of Yugoslavia and personally lobbied Presidents Truman, Eisenhower and Johnson to issue immigrant visas for German-Hungarians who had been held in labor and internment camps where thousands died as part of Yugoslavian President Tito’s plan to rid his country of ethnic Germans., Many of the players for the German-Hungarians and their rival Blau Weiss Gottschee in the fifties, sixties and seventies were either refugees, or the children of refugees.

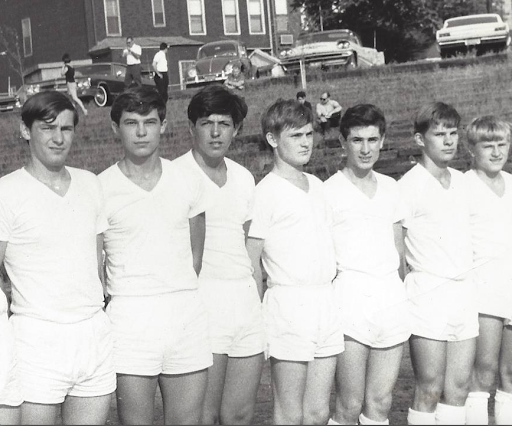

Werner Roth, second from the left, lines up at Metropolitan Oval

(Photo Courtesy of Rudy Jonke, Jr.)

Among this group, Roth stood out. After joining the German-Hungarians at age 8, he spent countless hours playing at the Oval where he matured into a standout defender. In 1972, he was chosen along with other stars from the German American Soccer League (GASL) to join the relatively new North American Soccer League (NASL). The kid from Ridgewood was signed by the New York Cosmos where he found himself playing alongside Pele and Franz Beckenbauer. Roth eventually captained the team of soccer legends to a “Soccer Bowl” title in 1977. Film buffs may also remember him as “Baumann” the Captain of the German team in the classic Sylvester Stallone soccer movie: Victory.

At a monthly gathering of former German-Hungarian and Gottschee players at Manor Oktoberfest restaurant in Queens, many recalled Metropolitan Oval’s outstanding atmosphere on game day, especially during the 60s and 70s, when the German-Hungarians were hosting the Greeks in New York’s Cosmopolitan Men’s League. On Sunday afternoons, after attending church services, over 3000 fans would come to worship at another altar by paying a buck or two to cram into the shed that ran along the south end of the field or open-air bleachers to the North. Some stood or sat on the hill to the East which had old wooden railway ties for benches. There was lots of cheering and emotion on all sides. Ricky Kren said fights on and off the field were common.

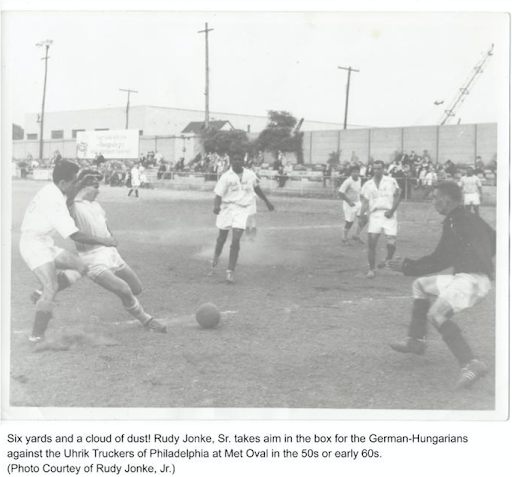

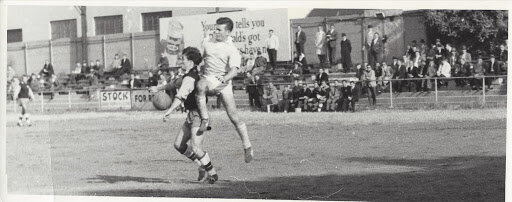

Rudy Jonke, Sr. in white, competes for the ball. (Photo Courtesy of Rudy Jonke, Jr.)

According to Gottschee goaltender and NASL veteran, John Grasser, the Greek men tended to wear suits, but that didn't keep them from getting dirty during half-time impromptu pickup games. Everyone wanted to get in on the act! German beer and bratwurst were on sale at the concession, and those who were looking for more fortification, could order a "tee mit” meaning “tea with.” or, more specifically, tea with Asbach, a German brandy. If you hit a wild shot over the goal that made it the parking lot, the crowd would jeer and someone would call out “Weiselbaumer!" in honor of a player who had a similar tendency. Home fans called rivals Kollsman Sport Club holzhacker (wood choppers) because they fouled so much. Beloved First Team Coach, Rudy Jonke, Sr. used to shout at his players when they held it too long in the back, “don’t fiddlely, #@$%! around with it!” This sentiment still holds among coaches and parents alike.

In a phone call Rudy Jonke, Jr., who still runs an auto repair shop in Glendale, Queens, remembered how after hard fought games at the Oval, the German-Hungarians would often invite their opponents back to the Club House at 576 Fairview in Ridgewood where they would shower and change in a basement locker room thick with the smell of Bengay. Then, they’d head upstairs to the bar, restaurant to talk about the game over Schaefer beer, schnitzel and other German delicacies. Jonke, Jr. also recalled how big crowds would turn out at Met Oval every Fall, when the German-Hungarians would celebrate Oktoberfest with traditional music, food, beer, dancing and soccer. Life was good!

Early Years

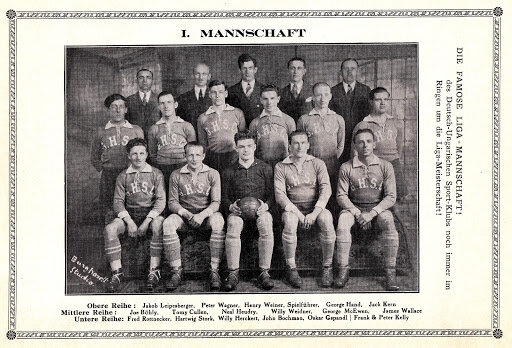

It took generations for Met Oval to become what Cosmopolitan League President, Peter Strumpf, described as “the soccer center” of New York. In the 1930s, the German Hungarian Club began making a name for themselves in the burgeoning American soccer scene. With their own ground and a steady stream of experienced players from the old country, the club was able to field a men’s team in the GASL, a semi-professional league with teams from Brooklyn, Hoboken, Queens, Manhattan, Newark and Elizabeth. There were no women’s leagues in the US at that time, so fielding a girls team was not considered. Instead, women and girls supported the men and boys on the sidelines and through the Ladies Auxiliary. As the name suggests, the league featured mostly German and Central European immigrants. At a time when anti-immigrant sentiment was on the rise in America, soccer was seen as "un-american", so many athletes avoided the game, choosing instead to play more “American" sports like baseball and basketball. Despite this, a critical mass of diehard players and fans allowed the league to survive the Great Depression.

Many of the German-Hungarian players worked in the local knitting mills making cotton and wool sweaters, so their team became known as “the Knitters”. Between 1930 and 1942, the Knitters won six men’s championships, and the club also added a Junior team for players ages 16-19 and a Boys team for players ages 14-16. Youth soccer at Met Oval had begun.

Soccer continued at Metropolitan Oval during World War II, despite losing considerable numbers of men to the war effort. In 1948, the owners of the ground, Kollsman Sport Club, informed the German-Hungarians that they were selling the field, and the only way the club could continue to use it, was if they bought it. The asking price was $30,000, over $300,000 in 2020 dollars. Fortunately, the war had been good to Club President Peter Max Wagner whose Rimax Knitting Mill landed contracts to make sweaters for the military. Wagner and other club members not only came up with the asking price, but they also raised $20,000 to improve the field. In photos from 1962 you can see that, not long after buying the field, the club built a cinder block concession stand and bathrooms which remain to this day.

Peter Max Morgan, Hellen Korrell, Helen and Fred Dindinger in 1946 outside an old entrance to Metropolitan Oval on Andrew st. (Photo Courtesy of Rudy Jonke, Jr.)

In 1951, another group of ethnic German immigrants, the Gottscheer from what is now Slovenia, formed their own soccer club, Blau Weiss Gottschee, and joined the GASL. Like the German-Hungarians, the Gottscheer were refugees from Yugoslavia in the wake of World War II. This was the beginning of a fierce rivalry that Met Oval continues today. In a phone interview, Ricky Kren’s lively eighty-three year-old German-Hungarian mother, Katie, a refugee from Yugoslavia, said that during sixty-one years of marriage, she and her husband, Arnold, a Gottscheer, always sat next to each other in the middle of the stands when the rivals played, but each sat on the side of their native region. Love conquered all, but identity mattered.

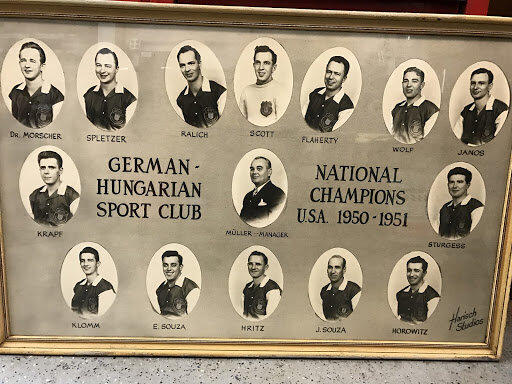

National Champions

In the same year that Gottschee formed, the German-Hungarians committed to developing a men’s team that could compete on a national level. For the 1951 season, they reached outside of New York and recruited two ringers from the professional American Soccer League (ASL): John Souza and Eddy Souza. The descendents of Portuguese immigrants from Ponta Delgado Soccer Club in Fall River, Mass, both John and Eddy had played for the US National Team in their historic 1-0 victory over England in the 1950 World Cup in Brazil. The new, non-German, talent propelled the club to titles in the GASL, the U.S. Amateur Cup, and the National Challenge Cup, what we now call the U.S. Open Cup. In the latter the Knitters defeated the Golden Tornadoes from Heidelberg, Pittsburgh on aggregate with a 6-2 demolition in front of the home crowd at Met Oval.

This would be the German Hungarian’s only national title, but in the 60s, 70s and 80s the Oval remained a home for great soccer players. European clubs like Hamburg and Stuttgart chose the field for exhibitions on their U.S. Tours. Walter Bahr from the 1950 US World Cup team played there. Future NASL professionals like Werner Roth and Ricky Kren practically grew up there. Captain of the 1990 U.S. Men’s National Team, Mike Windischman, featured at the Oval for Gottschee in his youth and national team members Tab Ramos and Tony Meola also knew what it was like to pick some Oval gravel out of their knees. Some have speculated that Pele himself may have graced the field. Sadly, there’s no evidence of that, but his son Edson Nascimento did appear there as a youth before going on to play professionally for Santos in Brazil. Remarkably, Pele’s Brazil and Cosmos teammate, Carlos Alberto, played at the Oval in the 80s for a German-Hungarian team that brought in outside talent including German great Gerd Muller to make a run at the over 30 US Open Cup. Despite having two legendary World Cup Champions on the squad, they lost in the finals.

1970 World Cup Champion, Alberto Carlos (Center) enjoying a post-game cigarette at the Oval with NASL and US Men's National Team player, Siggi Stritzl on his left and German Hungarian President, Jack Schaffhauser on his right. (Photo Courtesy of Rudy Jonke, Jr.)

Met Oval Under Threat

In the 80s and 90s the German-Hungarians struggled to maintain their membership as families began moving away to the suburbs. At the same time, immigrants from Latin America were arriving as part of a larger wave of global migration that would eventually make Queens the most ethnically diverse county in the United States with more languages spoken than anywhere else in the World., The new arrivals began renting the field for games and practices from the German-Hungarians, and a new group of avid fans began flocking to the Oval to see teams like Los Millonarios, Los Incas and Deportivo Cali. According to Club Treasurer, George Ritter, the games were played at night under the lights, and the atmosphere, fueled by food and beer, was festive. Soon, the Maspeth neighbors began complaining about the noise and the people. A 1994 New York Times article described how the mostly white community of Maspeth was simply uncomfortable with and unwelcoming to people from a different culture in their neighborhood. Community complaints forced the German-Hungarians to stop scheduling night games, and so they lost a significant source of income for the club from both field rental and the food and beer concession which they managed.

At the same time that Met Oval was gasping for air, the United States Soccer Foundation (USS Foundation) was sitting on nearly $50 million in proceeds from the 1994 FIFA World Cup with a clear mission to develop existing and new fields. The two seemed like a match made in heaven. At least, that’s what Soccer America’s Paul Gardner argued in a 1997 column in which he called the USS Foundation to save the field. Gardner encapsulated the essence of the field when he wrote:

There’s something about the place that draws soccer people to it. It’s somewhere that soccer people can feel at home. Where the ghosts of bygone games and a bygone era assure you that there is a sturdy past on which to build the future of American soccer.

The club applied for a USSF grant in that same year only to be turned down for unknown reasons. Past or not, Met Oval’s future looked unsturdy.

By 1999, the club, which never had not-for-profit status, owed New York City close to $400,000 in back taxes. Facing foreclosure, George Ritter said the club membership had no alternative but to sell the field. They were entertaining offers from a local public school and a Volkswagen dealership, when Jim Vogt, a former player and President of the Cosmopolitan Junior League, learned the field he had played on since age 7 was in trouble. Vogt reached out to Charles and Valerie Jacob, lawyers and owners of the Brooklyn Knights, a semi-professional soccer team. Vogt and the Jacobs made the pitch to club shareholders that, because of the tax debt, they would get nothing from the sale of the property. But, if they voted their shares to the newly formed, not-for-profit Metropolitan Oval Foundation, they could keep soccer alive at the historic field. Many of the members were the descendents of the original founders of the club, and had played at the field themselves. For them the choice was simple, soccer had to continue at the Oval.

Even though the Met Oval Foundation now owned the field, they still had to raise money to pay the outstanding tax bill to avoid foreclosure. As luck would have it, New York City’s Deputy Commissioner of Finance, Peter Lempin, had also played at the Oval for Astoria’s Bryant High. Lempin kindly agreed to postpone the foreclosure for a few years which gave the Foundation time to get a mortgage from Maspeth Savings Bank to pay the tax bill. It helps to have soccer friends in high places.

It also helps to have a crusading journalist nipping at the heels of the powers that be, and Soccer America’s Paul Gardner was just that. His article “Midnight Nears for Met Oval” accusing the USS Foundation of ignoring inner-city fields in favor of the suburbs, got the attention of the Secretary-General of the United States Soccer Federation (USSF), Hank Steinbrecher, who, shocking as it may seem, also played at the Oval as a kid. According to the Times, Steinbrecher said “…whenever I smell German cooking, I think of the Oval.” In 2000, at Steinbrecher’s urging, the USS Foundation came around and partnered with Nike and FieldTurf to pay for and install a state of the art artificial turf field at the Oval. After raising additional money to upgrade the lighting system, the Metropolitan Oval Foundation re-opened the Oval in 2001 with a mandate to provide a soccer facility and training for the youth. The new turf field played more like a grass field than astroturf and was a dramatic improvement over the “Dust Bowl.” The Oval received the ultimate soccer sanction when in the Fall of 2001, then FIFA President, Sepp Blatter visited the historic field prior to meetings at the United Nations and referred to the turf as the “future” of the game.” Just two years earlier, Met Oval was on the verge of becoming a memory, but love of the game, nostalgia for the old field, and a little bit of luck conspired to revive the aging institution and insure its future.

In 2007, Metropolitan Oval was one of the first clubs in the nation to be chosen as a United States Soccer Federation (USSF) Development Academy. According to the USSF, the goal of the Academy is to “create a more structured player development environment for elite players to develop to their highest potential.” Current Met Oval Sporting Director, Jeff Saunders, became a board member in 2012 after his son joined the club. A two-time All American at Hobart who played in Europe, Saunders pushed the board to keep its commitment to creating a “Youth Center of Excellence” based on the unique facility which the club controlled. Met Oval is one of the few clubs in the city that own their field. In 2013, at Saunders’ urging, the Club brought in English Professional Manager Paul Buckle to be Technical Director. At this time, the entire coaching staff was made up of professionals, as opposed to volunteers. When Buckle returned to England to coach in 2014, the Club appointed in his place a former Italian professional and Technical Director of AC Milan’s Junior Camps, Filippo Giovagnoli.

Under Giovagnoli’s watchful eye, Met Oval’s Youth Center of Excellence has become the leading player development academy in the region. In the past four years, since 2016, over 45 players have signed with professional academies domestically or internationally. Met Oval is the top affiliate partner of New York City Football Club, placing more players in the club than any other team. In 2018, Oval standout Justin Haak, became only the third home-grown player to sign with NYCFC. Youth national teams have selected over 20 Met Oval players to join them in competitions and training camps. More than 100 Met Oval kids have gone on to play in college.

And the future looks bright. Met Oval has established satellite clubs in Brooklyn and Long Island to identify regional talent. For the 2019/20 season, the club fielded girls teams with players born between 2007 and 2011. Similar to the boys, the plan is to identify and develop girls who will be part of the next generation of college and professional players.

Visit Met Oval today, and you’ll see the club is busy making improvements to the site. The parking lot which once looked like a World War I battlefield and wreaked havoc on many a shock absorber, now has a generous layer of gravel. Soon, construction will begin on a new building to house a gym for both weightlifting and injury recovery. On any given day, hundreds of kids, whose families come from all over the globe, are gathering at Metropolitan Oval to play the world’s game with an unbeatable view of the Empire State building. Nearly a century after the German-Hungarians first moved in, the future of one of American soccer’s oldest homes is secure.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the following for inspiring me, helping me or both!

Clare Bacon, Paul Gardner, John Grasser, Harry Gratwick, Chuck and Valerie Jacob, Rudy Jonke Jr., Ricky Kren, Katie Kren, George Ritter, Werner Roth, Jeff Saunders, Paul Strumpf and Mike Woitalla.

Special thanks to my son, Clyde, for joining Met Oval in the Spring of 2018 and giving me the chance to learn about this special place.

Extra Special thanks to my father and first coach, David Felsen, Sr., for starting me on my soccer journey on the fields of Haverford College a thousand years ago.